by Kenneth Hong

July 16, 2023

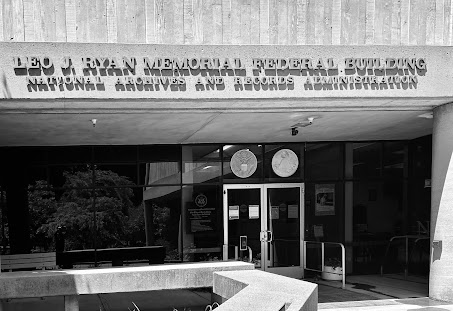

As I wind my way up Interstate 280, I take in the golden hills of California and glimpses of the Bay through the cool fog of an ordinary San Francisco summer morning. Exiting the highway, I drive by the rows of regimented white tombstones of the Golden Gate National Cemetery and up to the gray concrete bunker that is the National Archives. The usual feelings of anticipation build, a mixture of excitement and dread--excitement that I might find something new and dread that I end up with empty folders.

|

|

Entrance to the National Archives in San Bruno, CA July 3, 2023 |

This time, I have largely dodged the real prospect of coming up empty. The archivist have located the Chinese Exclusion Act era immigration files* for my maternal grandfather, both of his wives, but nothing for his father. What I get are files that I have never seen before.

The research room at the National Archives is open by appointment only. Researchers contact the Archives ahead of time, which allows the archivists to perform an initial search. If they have something, researchers make an appointment and take a test to certify they understand the strict safety and security protocols. No jackets or bags. No pens or books. Only approved single sheets of paper. No flash photography. No photographing the room or researchers. Review one file at a time. Keep the pages in order. You get the idea.

Thank goodness for smart phones. Remember to bring your charger (I didn't on my first day).

I pull out the first file and slowly, nervously flip though the pages. Most documents are typewritten on extremely thin onion paper. Some documents are fastened together. Most photos, loose or attached to documents, are in clear sleeves. I ask questions. Can I take items out of the sleeves? Yes. How do I photograph items that are fastened together? They carefully unbind the pages for me.

I take care to keep these national and personal treasures intact.

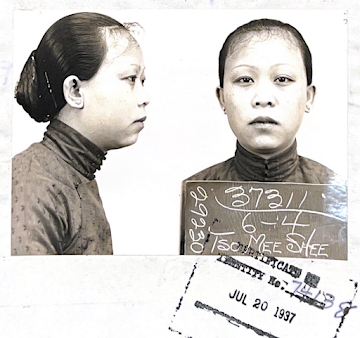

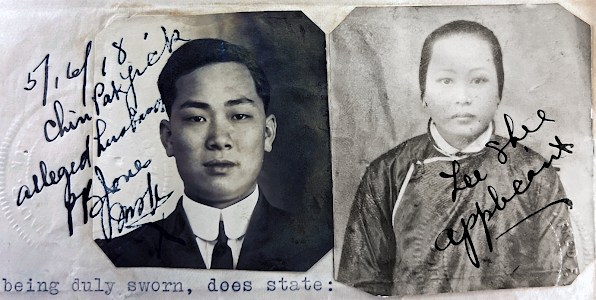

I am overjoyed at finding so much new information. New photographs of my family when they were young and full of possibility. A photo of my great-grandfather in my grandfather's file. Forms with personal details. Legal affidavits. Letters to and from family members. Interview transcripts from my great-grandfather, my grandparents, and their Chinese and white witnesses.

Experienced researchers know how to use their time at the Archives efficiently. They get a folder and the meticulously scan or photograph everything then review them at their leisure. In my excitement, I stop to skim through the documents trying to glean a little bit of what they might hold.

I read through my great-grandfather's transcripts and learn that he first arrived in the US aboard the SS China on November 26, 1910. I learn about his work as a merchant in a jewelry and watch store, its name and address. I learn similar details about my grandfather. I see wonderful original photographs of my grandfather's first wife and sadly, her 1933 death certificate. I find their wedding date and read their descriptions of the ceremony and how she lived with his mother while he lived at school from Monday through Saturday. After arriving in the US, he studied at the Lincoln School in Oakland. The same school as my mother. Wow!

The transcripts are dense, single-spaced, and can go on for 20 or 30 pages. There are documents in duplicate and triplicate. It is too much. It's now 1 pm and the Archives are closing at 3 pm, an hour early. It's the day before the 4th of July, and they are understaffed. I begin once again to methodically photograph the pages without reading them.

When I'm done I ask the archivist to look for my great-grandfather's file once again, this time armed with the date of his arrival and the name of his ship. We make another appointment for Friday in case they find anything. After looking through the documents which mention my grandfather's brothers, I ask them to look for his older brother who is buried in South San Francisco and for his famous first cousin. They find a thin file for my great-grandfather with nothing new, a thick file for my grandfather's cousin, and nothing for my great-uncle.

|

|

Outside the iron fence surrounding the National Archives July 7, 2023 |

When I have time to sift through my copies, and the exhilaration fades and turns to sadness and grief as I see the transparent purpose behind all of the photographs and interviews. I see the intrusiveness of the Immigration Service examiners and the lengths to which they went to ferret out any inconsistency between the "alleged husband", his "alleged wife", his business partners, and their corroborating Chinese and white witnesses. The use of language was deliberate. The Immigration Service made no presumption of innocence. Everything was alleged or suspect until they judged otherwise.

They asked for detailed descriptions about my grandfather's village not out of curiosity or interest but in order to find disagreement between the applicant and other witnesses regarding the layout of the village, who the neighbors were, and who stayed in which room of their house. There were lengthy discourses on my great-grandfather and grandfather's business and partners. Two white witnesses were required to attest that they were in fact merchants, who were allowed to be in the US under the Chinese Exclusion Act, and not laborers, who were not. Hands were inspected for calluses. After lengthy first interviews, the alleged husband and wife had to be recalled more than once to pursue new lines of questioning or cross check facts.

Then I came across a relatively short 11 page transcript from May 4, 1936, covering the interviews of ten people. Not too bad you might say. That's barely one page per person. The interviews were for my grandfather and all of my uncles and aunts.

On that May day in 1936, 2 1/2 years after his wife died, my widowed grandfather with his nine native-born American children, ages 5 to 16, took a ferry to the Angel Island Immigration Station. They then, in turn, sat through an interview about their alleged parents and siblings. Each interview started something like this:

Q What is your name?

Q How old are you?

Q When and where were you born?

Q Who is your father?

Q Who is your mother?

Q Where is your mother?

Q Describe your brothers and sisters?

Q Where do you live?

Q Do you go to school?

Q How about your brothers and sisters?

The younger children had fewer questions; the older ones more. For example, names and ages of their siblings, where they had lived previously, what they knew about their grandparents, and their father's work. The transcript also included a physical description of each of them including height, hair and eye color, complexion, and scars and moles on their faces and hands.

William, age 5, signed his interview with an "X". The older kids signed their names in English and Chinese. Elsie had the best penmanship in both languages. Helene, age 6, could not identify a file photograph (probably taken 18 years earlier) of her mother who died when she was 3. Henry and Morris could not do this either. The children give slightly different ages for each other. The younger ones didn't know the year they were born, and Henry, age 7, gets his birth month wrong. Edith, age 15, was the only one who knew that their grandmother was still alive in China and that their grandfather had died.

After I share the transcript with a cousin, she comments about her mother Helene's interview with familiar feelings of pride, confusion, curiosity, and outrage:

"She knew most of the answers."

"She didn’t even come into the country, she was born here. Doesn’t make sense!"

"It’s still cool stuff."

"I don’t know how the interviewers expected 5- and 6-year-old kids to answer those types of questions."

They asked those types of questions because they were just doing their jobs in

an immigration service bureaucracy build around the Chinese Exclusion Act,

which was the law of the land for the 61 years from 1882 to 1943.

|

Gallery of New Photos from the National

Archives.

|

No comments:

Post a Comment